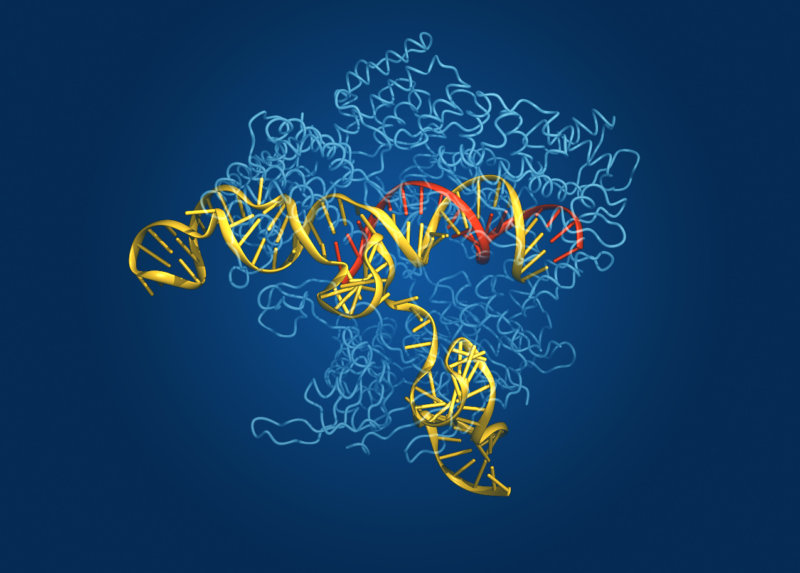

Enlarge / The protein structure of CAS, shown with nucleic acids bound. (credit: Bang Wong, Broad Institute)

CRISPR—Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats—is the microbial world’s answer to adaptive immunity. Bacteria don’t generate antibodies when they are invaded by a pathogen and then hold those antibodies in abeyance in case they encounter that same pathogen again, the way we do. Instead, they incorporate some of the pathogen’s DNA into their own genome and link it to an enzyme that can use it to recognize that pathogenic DNA sequence and cut it to pieces if the pathogen ever turns up again.

The enzyme that does the cutting is called Cas, for CRISPR associated. Although the CRISPR-Cas system evolved as a bacterial defense mechanism, it has been harnessed and adapted by researchers as a powerful tool for genetic manipulation in laboratory studies. It also has demonstrated agricultural uses, and the first CRISPR-based therapy was just approved in the UK to treat sickle-cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia.

Now, researchers have developed a new way to search genomes for CRISPR-Cas-like systems. And they’ve found that we may have a lot of additional tools to work with.

Read 12 remaining paragraphs | Comments