When human stem cells were discovered at the turn of the century, it sparked a frenzy. Scientists immediately dreamed of repairing damaged tissues due to aging or disease.

A few decades later, their dreams are on the brink of coming true. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved blood stem cell transplantation for cancer and other disorders that affect the blood and immune system. More clinical trials are underway, investigating the use of stem cells from the umbilical cord to treat knee osteoarthritis—where the cartilage slowly wears down—and nerve problems from diabetes.

But the promise of stem cells came with a dark side.

Illegal stem cell clinics popped up soon after the cells’ discovery, touting their ability to rejuvenate aged skin, joints, or even treat severe brain disorders such as Parkinson’s disease. Despite FDA regulation, as of 2021, there were nearly 2,800 unlicensed clinics across the country, each advertising stem cells therapies with little scientific evidence.

“What started as a trickle became a torrent as businesses poured into this space,” wrote an expert team in the journal Cell Stem Cell in 2021.

History is now repeating itself with an up-and-coming “cure-all:” exosomes.

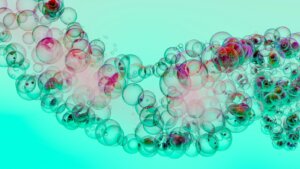

Exosomes are tiny bubbles made by cells to carry proteins and genetic material to other cells. While still early, research into these mysterious bubbles suggests they may be involved in aging or be responsible for cancers spreading across the body.

Multiple clinical trials are underway, ranging from exosome therapies to slow hair loss to treatments for heart attacks, strokes, and bone and cartilage loss. They have potential.

But a growing number of clinics are also advertising exosomes as their next best seller. One forecast analyzing exosomes in the skin care industry predicts a market value of over $674 million by 2030.

The problem? We don’t really know what exosomes are, what they do to the body, or their side effects. In a way, these molecular packages are like Christmas “mystery boxes,” each containing a different mix of biological surprises that could alter cellular functions, like turning genes on or off in unexpected ways.

There have already been reports of serious complications. “There is an urgent need to develop regulations to protect patients from serious risks associated with interventions based on little or no scientific evidence,” a team recently wrote in Stem Cell Reports.

Cellular Space Shuttles

In 1996, Graça Raposo, a molecular scientist in the Netherlands, noticed something strange: The immune cells she was studying seemed to send messages to each other in tiny bubbles. Under the microscope, she saw that when treated with a “toxin” of sorts, the cells slurped up the molecules, planted them on the surfaces of tiny bubbles inside the cell, and released the bubbles into the vast wilderness of the cell’s surroundings.

She collected the bubbles and squirted them onto other immune cells. Surprisingly, they triggered a similar immune response in the cells—as if directly exposed to the toxin. In other words, the bubbles seemed to shuttle information between cells.

Dubbed exosomes, scientists previously thought they were the cell’s garbage collectors, gathering waste molecules into a bubble and spewing it outside the cell. But two years later, Raposo and colleagues found that exosomes harvested from cells that naturally fight off tumors could be used as a therapy to suppress tumors in mice.

Interest in these mysterious blobs exploded.

Scientists soon found that most cells pump out exosome “spaceships,” and they can contain both proteins and types of RNA that turn genes on or off. But despite decades of research, we’re only scratching the surface of what cargo they can carry and their biological function.

It’s still unclear what exosomes do. Some could be messengers of a dying cell, warning neighbors to shore up defenses. They could also be co-opted by tumor cells to bamboozle nearby cells into supporting cancer growth and spread. In Alzheimer’s disease, they could potentially shuttle twisted protein clumps to other cells, spreading the disease across the brain.

They’re tough to study, in part, because they’re so small and unpredictable. About one-hundredth the size of a red blood cell, exosomes are hard to capture even with modern microscopy. Each type of cell seems to have a different release schedule, with some spewing many in one shot and others taking the slow-and-steady route. Until recently, scientists didn’t even agree on how to define exosomes.

Over several years, the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles, or exosomes, has begun uniting the field with naming conventions and standardized methods for preparing exosomes.

The Wild West

While scientists are rapidly coming together to cautiously make exosome-based treatment a reality, uncertified clinics have popped up across the globe. Their first pitch to the public was tackling Covid. One analysis found 60 clinics in the US advertising exosome-based therapy as a way to prevent or treat the virus—with zero scientific support. Another trending use has been in skin care or hair growth, garnering attention in the US, UK, and Japan.

Exosomes are regulated by the FDA in the US and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in the EU as biological medicinal products, meaning they require approval from the agencies. That did not stop clinics from marketing them, with tragic consequences. In 2019, patients in Nebraska treated with unapproved exosomes became septic—a life-threating condition caused by infection across the whole body—leading the FDA to issue a warning.

Clinics that offer unregulated exosomes “deceive patients with unsubstantiated claims about the potential for these products to prevent, treat, or cure various diseases or conditions,” the agency wrote.

Japan is struggling to catch up. Exosomes are not regulated under their laws. Nearly 670 clinics have already popped up, representing a far larger market than the US or EU. Most services have been marketed for skin care, anti-aging, hair growth, and battling fatigue, wrote the authors. More rarely, some touted their ability to battle cancers.

The rogue clinics have already led to tragedies. In one case, “a well-known private cosmetic surgery clinic administered exosomes…to at least four patients, including relatives of staff members with stage IV lung cancer, and found that the cancer rapidly worsened after administration,” wrote the authors.

Because the clinics operate on the down-low, it’s tough to gauge the extent of harm, including potential deaths.

The worry isn’t that exosomes are harmful by themselves. How they’re obtained plays a huge role in safety. In unregulated settings, there’s a large chance of the bubbles being contaminated by endotoxins—which trigger dangerous inflammatory responses—or bacteria that lingers and grows.

For now, “from a very basic point of view, we don’t really know what they’re doing, good or bad… I wouldn’t take them, let’s put it that way,” James Edgar, an exosome researcher from the University of Cambridge, told MIT Technology Review.

Unregulated clinics don’t just harm patients. They could also set a promising field back.

Scientific advances may seem to move at a snail’s pace, but it’s to ensure safety and efficacy despite the glitz and glamor of a potential new panacea. Scientists are still forging ahead using exosomes for multiple health problems—while bearing in mind there’s much we still need to understand about these cellular spaceships.

Image Credit: Steve Johnson on Unsplash